I never thought I would be a poet. When I was beginning my full immersion into writing, and dedicating myself to the craft, I had already made up my mind that I was a fiction writer. I adored fiction because I thought it was the best place to create worlds. It had a more massive scope to build, and I just didn’t associate that with poetry. Prior to my entanglement in poetry, I thought it was basically this fancy, condensed, intellectual beast I wouldn’t ever really be able to tap into.

I never thought I would be a poet. When I was beginning my full immersion into writing, and dedicating myself to the craft, I had already made up my mind that I was a fiction writer. I adored fiction because I thought it was the best place to create worlds. It had a more massive scope to build, and I just didn’t associate that with poetry. Prior to my entanglement in poetry, I thought it was basically this fancy, condensed, intellectual beast I wouldn’t ever really be able to tap into.

It wasn’t until my junior year, and even more so, my current senior year in creative writing at Douglas Anderson, that I really found out I had a poetic voice. What I learned mostly, from my poetry classes, as well as from constantly reading the work of my peers, is that fiction isn’t the only place for a narrative. Poems can be wombs which birth stories whether it be concrete or not, and even if a poem feels confusing, an emotional narrative is always apparent.

The concept of an emotional narrative is something that I hold very dear to me. Within my poetry, I at first felt daunted by trying to get across what I desired to say. In fiction you’re able to have more room to build context, to play around, and lead up, but within poetry the collective piece is attempting to get the reader to feels something and pull them in, in a limited space. Poems of course, don’t have to be short, they can be expansive creatures, though typically, they aren’t as long as a novel.

To try and tackle the task for formulating an emotional structure to which my poems flow, I normally start off with creating some type of setting or atmosphere. In a lot of my poems, I’m setting the scene to what I’m going to show. I often use color in my pieces too, to visualize what I want myself and others to feel when they read my poem. I like to think of the type of color I want to show with my words, its softness or sharpness, the depth of the color, and how can I construct the words around it to sound fluid or sharp to enhance that color.

Thinking about things like colors, then help me build the narrative I want to be contained inside my poem. Along with the rest of what’s going on I construct the words meaningfully, create line breaks to control the pacing of the piece, and I’ve learned to manipulate structure to do my bidding.

Poetry is very flexible. I am in love with traditional looking poems, but also the prose poem. Poems have many designs and costumes to wear, as within prose poems it can mimic the reading style one takes on when reading normal prose, but syntax doesn’t have to be confined to conventional methods. One doesn’t have to build an actual story but have a fluid contemplation in that form. It can stabilize a moment. Regardless though, at the end of the day, the work is still poetry, and it’s working on undressing itself and to give the reader permission, to uncloak themselves too, to their own vulnerabilities to expose some type of truth at the end.

I may have started out a fiction writer, but I am an equally strong and dedicated poet. Poetry has aided me in exposing the truths I never wanted to confront ever, because in the smaller space you can only run from our minds so much that eventually you have to take the sword to the dragon.

-Kiara Ivey, Layout and Design Editor

I love the word “brevity.” It’s quick and sharp but still flows well. It sounds like someone had the guts to let out what they wanted to say. It’s also the word Scholastic’s Art and Writing contest uses to describe flash fiction, and I’d say that’s accurate.

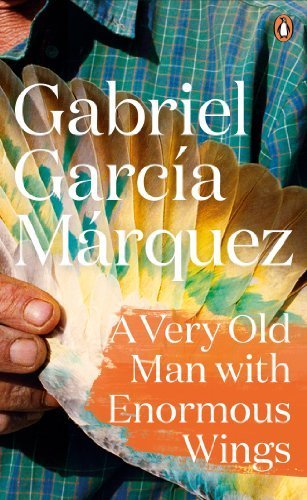

I love the word “brevity.” It’s quick and sharp but still flows well. It sounds like someone had the guts to let out what they wanted to say. It’s also the word Scholastic’s Art and Writing contest uses to describe flash fiction, and I’d say that’s accurate. When I was first introduced to the magical realism genre, I thought it was strange and knew right away that I wouldn’t like it. However, after studying it for a few weeks in my creative writing class, and eventually writing my own story within the genre’s definition, it became one of my favorite things to write about. I love the idea of being able to take a cliché topic and make it original in its own world.

When I was first introduced to the magical realism genre, I thought it was strange and knew right away that I wouldn’t like it. However, after studying it for a few weeks in my creative writing class, and eventually writing my own story within the genre’s definition, it became one of my favorite things to write about. I love the idea of being able to take a cliché topic and make it original in its own world.