The first poem I ever wrote still hangs on my grandmother’s wall. I found it there a few weekends ago, while staying in her guestroom. “Tiger Eye Sun” is the title, printed in a special font on computer paper. I wrote it in a public library workshop when I was six. I remember the adults clapping when I finished reading it out loud. I loved twisting the images of rocks, and playing with personification, to describe something to simple and routine as the sun. I was able to take something I thought was familiar, and show it in a different way. This made me want to be a writer.

The first poem I ever wrote still hangs on my grandmother’s wall. I found it there a few weekends ago, while staying in her guestroom. “Tiger Eye Sun” is the title, printed in a special font on computer paper. I wrote it in a public library workshop when I was six. I remember the adults clapping when I finished reading it out loud. I loved twisting the images of rocks, and playing with personification, to describe something to simple and routine as the sun. I was able to take something I thought was familiar, and show it in a different way. This made me want to be a writer.

The poem is, of course, full of the things expected of six year old writers. It doesn’t have images, so much as mentions, and the intent, if I ever had one, is quite clouded. But that doesn’t matter. If writing this piece made me want to stick with the craft, then it means something, in all its kindergarten glory.

Writing stayed my favorite subject in school, including many short stories, poems, and a few “novels” comprised of about thirty pages each. Still, I had no way of knowing if what I tried was any good–as good as an elementary school writer can be–until the seventh grade. That Christmas, I entered and won a Christmas story competition for the local newspaper. My piece was printed that holiday for the city to read. I was elated, and decided to keep on writing.

Now, I write every day, I’m in classes, learning the mechanics of line breaks and character development. Looking back on my old writing makes me cringe. But, like something really horrific on television, I can’t help but look. What’s interesting isn’t so much the ways I’ve failed at communicating a story, it’s the ways I’ve succeeded without realizing it.

Until high school, I didn’t think to make a distinction between summary and scene. They were all parts of a story to me. And still, that Christmas story, has managed to establish a backstory, then lift the character into a scene, then jump back again to transition or give context. I wondered, at first, if there was something intuitive to writing. But now, I don’t think so. If writing could be based purely on intuition, then there would be no need for teaching it. Instead, I was reminded of what my teachers, and the professional writers I’ve seen, have all said: read, read, read. My whole life has been partially consumed by books. My mother and father read to me at night. I checked out audio cassettes of the Harry Potter series and Beverly Clearly. I buzzed through the books at school. I learned how to write the basics of a story because I read.

So, if I could learn so much by reading, why is it that studying creative writing is still so important? Studying creative writing is not a “learning how to write”. A person can write without instruction. My teachers, instead, have showed me why choices are made, and what choices. Just reading only shows you the final product. A poetry class calls to attention everything that was put in, and everything that isn’t said. My teachers could take the words, which I might have appreciated on my own, and turn them into a whole working structure. Since high school, I’ve started to learn how to make choices, what counts. I can look at writing not just through my emotional response, but by the subtle pointers driving that emotion.

My early writings had no choices. I didn’t think when I wrote, I just saw something in my mind and recorded it. Like a kid who sees the prettiness of a flower. Now, I come across an idea, and I see it for the Fibonacci-driven fractal that it is: infinite, up to me to realize what should be shown, and what should influence the reader from the inside.

–Ana Shaw, Junior Editor in Chief

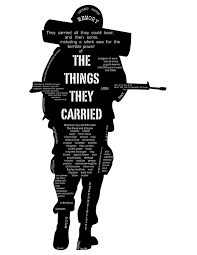

The first thing I was taught when I started writing was how to correctly use both diction and syntax to further the emotional response evoked from the reader. Emotion is something I really focus on when writing and I think it also gives me new ideas when I want to convey raw feelings. An author that I studied who is exceptional at this technique is Tim O’Brien, the author of

The first thing I was taught when I started writing was how to correctly use both diction and syntax to further the emotional response evoked from the reader. Emotion is something I really focus on when writing and I think it also gives me new ideas when I want to convey raw feelings. An author that I studied who is exceptional at this technique is Tim O’Brien, the author of